PART 52: The Sun and the Moon (January 1st, 1836 – January 7th, 1837)

Hu Ping, The Occident in Flames: Revolution and War in the Near West, 1802-1850, (Shanghai: Shanghai University Press, 2004)

Excerpts from Chapter Ten, Victorians and Capetians

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE CAPETIAN AND VICTORIAN LEAGUES

The War of the Victorian League (known to contemporary Chinese and Japanese observers as the “Occidental Crisis”) is simultaneously one of the most well-known and most frequently misconstrued conflicts in the first half of the 19th century. Eastern historiography in particular often falls back on essentially Occidentalist readings of the war’s roots, and these interpretations have in turn been reinscribed in Western histories.

The first of these reductionist views of the war is that it was simply a conflict between the conservative old order and newer liberal states– a struggle between absolutist monarchy and modern democracy. This position is best addressed by examining the protagonists of the war: the Victorian League and the Capetian League.

Gui de Valois-Vexin of France, Uschieh de Valois-Vexin of Poland, Jaime de Melo of Portugal

The Capetian League (named for the Capetian dynasty, of which the House of Valois is a cadet branch) is, indeed, undeniably reactionary and absolutist in character. This, however, has more to do with the total dominance of France amongst the three “brother kings” of the League. Poland, ruled by a junior branch of the Valois-Vexin, had long been firmly in the French orbit. The tiny island nation of Portugal’s war contributions were chiefly limited to naval logistics support and training less experienced French and Polish naval officers, so it could hardly be considered an equal partner in the Capetian League. So the reactionary character of the league was simply a reflection of France’s own politics, since the Capetian League itself was little more than an instrument of French hegemony.

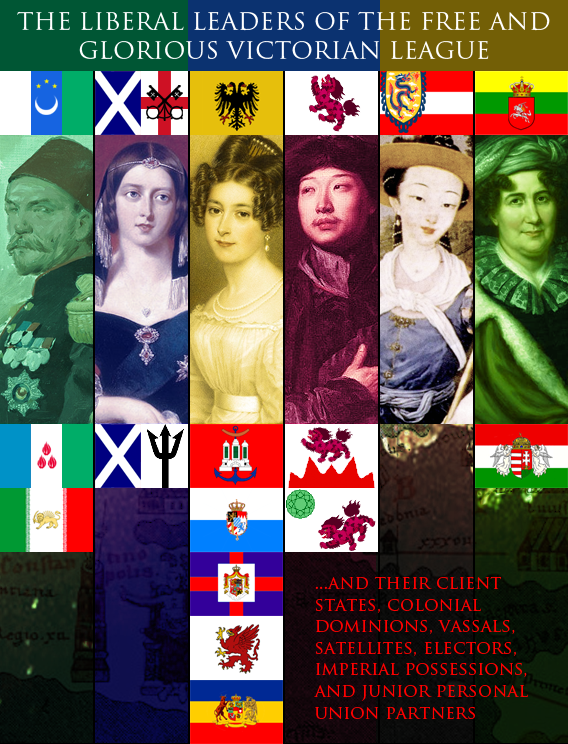

President Turhan Toraman of the Byzantine Republic; Victoria III von Habsburg, Queen of the British; Charlotte von Habsburg, Queen of the Romans; Sultan Lan II de León of Lai Ang; Sultana Xu Xiulan of Austria[1]; Queen Darate I Dunin of Lithuania-Hungary

Firstly, whilst the Byzantine Republic, Great Britain, and the Holy Roman Empire were all dominated by revolutionary liberal politics, the other Victorian League all had long traditions of constitutional monarchy independent of the 1802 revolution, the Golden Revolution, and the election of Charlotte von Habsburg. They were more liberal than France, but this was as much a function of France’s explicilty illiberal politics as it was through any deliberate political programme on their part.

The second thing that one notices about the Victorian League is the long train of satellites, spheres of influence, vassal states, “associate republics”, colonial dominions, crown territories, and other euphemisms for imperial holdings that followed most of the members into the war. The Byzantine Republic had the Azerbaijani Republic and Iranian Republic, both puppet states set up by the Byzantines to administer the eastern conquests of the late Roman Empire and early Republic. Great Britain controlled the dominion of Habsburg in Central Avalon (as well as various colonial possessions without even nominal self-governance, such as Nova Scotia or the Bahamas). The minor German states of Bavaria, Hamburg, Mecklenburg, Pommerania, and Oldenburg had all accepted Berlin as their overlord in term for a nebulous position as “electors” of the Holy Roman Empire. Lai Ang possessed the most extensive colonial empire of any Near Western power, and its dominions in Nuevo Xi’an and Tianhui Catalina duly joined the war effort. “Lithuania-Hungary” was simply a term for Lithuanian dominance and Hungarian sub-ordinance in the Dunin dual monarchy. Of all the allies, only Austria lacked vassal states to pressgang into the war– and it was by far the least significant of the major belligerents.

This brings us to the second major fallacy about the War of the Victorian League: that it was a struggle between the nascent nationalist movements of the nineteenth century and the sprawling multinational empires of the early modern era. But which side supported the nationalists and which was trying to hold together multinational dominions? A cursory look at the initial war goals of each side reveals that both sides sought to exploit nationalist sentiment within their rivals in such a way as to avoid empowering nationalists at home (the secessions of Ireland and New Bulgaria were fresh in all of the belligerents’ minds). France’s demand that Byzantium grant its restive Sicilian territories independence, therefore, was couched in terms of restoring the heirs of the murdered Queen Giuliana di Chios to the Sicilian throne. Meanwhile, the Byzantines’ sudden embrace of the Holy Roman Empire (which still, at least theoretically, claimed the translatio imperii with the Roman Empire, the destruction of which was the cornerstone of the Byzantine national identity) was a way to safely exploit unrest in French Germany to break the back of de Valois-Vexin dominance of Europe without endorsing nationalism in principle (lest the Sicilians, Croatians, Azerbaijanis, Persians, et al get any ideas)

PHASE TWO

As discussed in the last chapter, the War of the Victorian League technically began in late 1835, when Poland attacked Lithuania-Hungary, which was erroneously seen as a peripheral member of the Victorian League the Byzantines and British were disinclined to defend. The flurry of activity that took place on January 1st, 1836 is seen as the beginning of the war proper.

The National Assembly of Byzantium attempted to bolster its liberal credentials by creating a system of state-run trade unions, ostensibly because that seemed like the sort of thing the French wouldn’t do.

President Toraman had no illusions that war would be fast or easy. His General Staff had run extensive exercises and wargames to model war with France, and they anticipated a long, grinding war of attrition. He therefore signed legislation calling for a modernization of the medical infrastructure of the Republic– in particular, in implementing reforms to military medicine pioneered by the armies of Somalia and Ghana.

Finally, and most famously, he mobilized the general populace into the armed forces.

France answered in kind of a levée en masse of its own. France, however, had much more experience with such mass mobilizations of the population, who under the de Valois-Vexin system of governance were all part of a clear chain of feudal obligation to noble officers.

France also enjoyed the advantage of a much higher population than any other nation in the Near West. Globally, the manpower at the Capetians’ disposal dwarfed even that of states like Marathas, Somalia, Japan, or the Ayiti Federation– only the Ming Empire and Hindustan were more populous.

Combined, the Victorians still a larger population than the Capetians– but getting their citizens armed, trained, and to the front was often a logistical challenge.

Reinforcing allied armies still further afield was even more difficult.

The War of the Victorian League is best understood in terms of five fronts. The “southern front” was northern Italy, southern Germany, and southeastern France; the “western front” was along the Pyrenees and in northern Iberia; the “northern front” was the Cornwall, English Channel, and northern France; the “German front” was the defense of Holy Roman Imperial territory proper (and is a bit of a misnomer, as many of the decisive battles on the southern front were fought in Bavaria or Austria), and the “eastern front” was the continuation of the earlier war between the Dunin monarchy and Poland in the context of the larger continental war.

The Byzantine Expeditionary Force in the German theater proved invaluable in early Holy Roman Imperial victories, but it represented only a small portion of Byzantium’s overall military strength.

For the most part, Byzantium’s first priority was the defense of northern Italy and the invasion of southern Germany.

The bloodiest war in European history happening right on their doorsteps alarmed the minor neutral states of Italy, and the Sienese Republic collapsed into dictatorship.

In the north, the British quickly occupied French Cornwall, which the Capetians made no effort to defend– assuming that they’d simply be able to get it back in negotiations following a favorable peace. Instead, the French hoped to be able to hold the English Channel and prevent a British invasion of the Continent via the strait of Dover.

The Byzantines dispatched a fleet to aid the British and Lai Ang in securing the vital strait.

This went about as well as Byzantine naval adventures usually did– although, for once, the Byzantine navy avoided total annhilation, and the fleet limped to the captured port of Plymouth for repairs.

The land war, on the other hand, was going much better for the Byzantines, with victories being handily won along both the southern and northern fronts.

The defense of Northern Italy had become an invasion of southern France and Germany.

Buoyed by these successes, President Toraman was able to pass a second major political reform– the implementation of secret ballots in Byzantine elections– in the space of a single year.

Meanwhile, the tide on the eastern front was gradually turning in the Dunins’ favor. Interestingly, the main allied contribution to this front in the early war was a detachment of soldiers from the Azerbaijani Republic[2].

It is important to recognize the Victorian War in the context of global events. Observers in the Far West and Asia alike often take it as proof that Europe in the early-to-mid 19th century was an exceptionally savage, bloody, or chaotic region. So it should be remembered that while the Victorians and Capetians were duking it out in the Near West, an equally bloody war between the plague-stricken Ming state and the rising power of Hindustan broke out. The Sino-Hindustani War is much less remembered in popular culture, since exotic European (and Sino-European– remember Austria and Lai Ang) led by colorful historical figures like Victoria von Habsburg or Gui de Valois-Vexin are seen as much more picturesque than thousands of Indians and Chinese dying in a dispute over a barely-inhabited stretch of the Himalayas.

Meanwhile, the colonial dominions of the Ayiti Federation were in political turmoil, forcing the release of Cape Nitaino as an independent dominion.

Back in Europe– with northern Italy apparently secure, the Byzantines (bolstered by the arrival of Iranian troops from the eastern frontiers) began an offensive through Austria to liberate Capetian-occupied Bavaria.

And in the north, the Victorians had recovered from their earlier setbacks following the arrival of Lai Ang and Britain’s colonial fleets to European waters, and the Channel was secured, paving the way for future British landings in northern France.

On the southern front, however, the Byzantines had stretched their lines too thinly, and a French army was able to break through at the lightly defended city of Turin.

Meanwhile, the Byzantine advance into Bavaria was badly disrupted by an attempt to fend-off a French counteroffensive.

The Byzantines had the numbers to easily fend off these probing French attacks– but it forced them to abandon their earthworks and trenches and attack, more or less scuppering Toraman’s initial war plans to slowly advance a broad front across southern Capetian territory. The initiative on the southern front had passed into French hands.

The Hindustanis and British both reaped the benefits of the prestige of taking on the premier power of their respective continents in war.

In spite of the disruptions to their initial war plans on the southern front, the war was still going broadly in the Victorians’ favor.

Lithuania and Hungary (and Azerbaijan!) were slowly pushing the Polish west…

Lai Ang had already advances all the way to the Pyrenees…

…and while Byzantium was forced to abandon its advance into Bavaria, it managed to reorganize its frontlines and halt the French counter-offensive.

And that’s when Empress Yekaterina III of Russia decided to invade Scandinavia and Lithuania.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Nineteenth century Austria is still occasionally referred to as “Ao Di Li”, but by the War of the Victorian League this name had been anachronistic for centuries. For a more in-depth discussion of Austria’s place in the Western world, see Adria Wu, “Three Approaches to Hui Cultural Fusion in the Near West: A Comparative Study of Austria, Lai Ang, and Da Qin in the Early Modern Era,” The Journal of the Ming Frontier Historical Society 4 (May 2003): 201-232.

[2] While not central to the main narrative of the war, the story of these Azeri soldiers is told in the eminently readable Konstantinos Tatopoulos’ Dying in a Cold Place: The Translated Letters of Cpt. J. Jahan (Athens: Athens University Press, 1978)